Neurodiversity as a foundation for care

Neurodiversity recognizes that neurological differences such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and dyslexia are natural variations of the human brain. Rather than viewing these differences solely as disorders to be corrected, this perspective emphasizes respect for individuality, autonomy, and functional well-being. In mental health care, this shift allows us to move beyond symptom control and toward approaches that support the whole person—biologically, emotionally, and socially (Hartman & Patel, 2020).

For individuals on the autism spectrum, this is particularly important. Neurodevelopmental differences affect not only cognition and behavior, but also digestion, immune function, sensory processing, and metabolism and vice versa. As a result, integrative approaches that include nutrition and physiology are essential for reducing distress and supporting quality of life.

Why are autism spectrum disorder rates increasing

The rise in ASD diagnoses cannot be attributed to a single cause. Increased awareness and changes in diagnostic criteria play a role, but they do not fully explain the trend (Taniya et al., 2022). Research suggests that multiple factors may interact during early development, including older parental age, environmental toxin exposure, maternal inflammation, medication use during pregnancy, and inadequate nutrient intake (Khashan & O’Keeffe, 2024).

Rather than one isolated trigger, ASD may emerge from a cumulative burden of stressors. Lemer (2014) describes this as “total load,” where physical stress, immune challenges, environmental exposures, and food sensitivities collectively strain the developing nervous system. Studies linking prenatal exposure to common medications and air pollution with increased ASD risk support this multifactorial view.

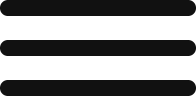

The gut–brain connection and diet

Digestive problems are extremely common in ASD and are closely linked to emotional regulation, sensory sensitivity, and behavior. Differences in nervous system regulation, immune activity, and gut microbiome composition can make the digestive system more vulnerable to inflammation and impaired nutrient absorption. Early life nutrition, including sensitivity to gluten, casein and infant formula, may also play a role (Bjørklund, Meguid, Hemimi et al, 2024), contributing to the opioid theory as causative.

For this reason, nutrition often becomes a key area of support. Personalized dietary approaches—such as gluten- and casein-free diets or gut-focused protocols—aim to reduce digestive stress and inflammation when gut function is compromised (Yu et al., 2022). These strategies are not meant to restrict unnecessarily, but to create a physiological environment that supports both gut and brain function.

Research has also identified frequent nutrient imbalances in ASD, particularly deficiencies in essential fatty acids and an imbalance between omega-6 and omega-3 fats, which are critical for brain health and emotional stability (Vancassel et al., 2001). When these imbalances are addressed, improvements in digestion, mood, and behavior are often observed.

Fats, inflammation, and brain function

Healthy fats play a central role in brain structure and communication. In ASD, inflammation and altered lipid metabolism may interfere with how these fats are used. Some individuals show signs of immune activation that affect brain function, reinforcing the importance of reducing inflammatory load through diet and lifestyle (Careaga et al., 2013).

Diets lower in refined carbohydrates and richer in anti-inflammatory fats—such as those found in fish oil, eggs, and phospholipid-rich foods—may help support more stable emotional and cognitive functioning (Bell et al., 2004).

Food Selectivity, Oxytocin, and Cholesterol

Selective eating is very common in ASD and is often related to sensory sensitivities, strong routines, or early digestive discomfort. Many individuals rely heavily on carbohydrate-rich foods because they feel safer or more predictable. Over time, this pattern can limit the intake of protein, calcium, and healthy fats—nutrients that are essential for brain development and emotional regulation (Sharp et al., 2013).

This becomes especially relevant when considering oxytocin, a hormone involved in social connection, emotional balance, and stress regulation. Some studies suggest that oxytocin activity may be lower in individuals on the autism spectrum (Gimpl & Fahrenholz, 2002). Because the body needs cholesterol to produce oxytocin, diets that are very low in fats may unintentionally reduce the brain’s capacity for emotional and social regulation. In some cases, improving lipid intake and overall nutritional balance has been associated with better behavioral stability and reduced reactivity (Aneja & Tierney, 2008).

Toward Personalized, Integrative Support

Research on nutrition and ASD continues to evolve, but one message is consistent: there is no single diet or supplement protocol that works for everyone. Each individual presents a unique combination of neurological traits, nutritional status, immune activity, gut health, and metabolic needs. For this reason, personalized assessment and targeted nutritional support offer the most effective and sustainable path forward. When biological imbalances are addressed within a framework that respects neurodiversity, care becomes more humane, responsive, and genuinely supportive of long-term well-being.

This blog draws from the latest edition of my book, Nutrition Essentials for Mental Health, where I examine how different mental health conditions are often linked to specific nutritional deficiencies and underlying biological patterns. These connections matter because psychological symptoms rarely exist in isolation; they are frequently influenced by physiological processes that remain overlooked in conventional care.

By integrating nutritional assessment with psychological evaluation, it becomes possible to identify contributing biological factors and design more precise, individualized interventions. Rather than relying on generalized recommendations, this approach supports care that is both evidence-informed and responsive to individual needs.

References

Aneja, A., & Tierney E. (2008). Autism: The role of cholesterol in treatment. International Review of Psychiatry, 20(2), 165–170. doi: 10.1080/09540260801889062.

Bell, J. G., MacKinlay, E. E., Dick, J. R., MacDonald, D. J., Boyle, R. M., & Glen, A. C. A. (2004). Essential fatty acids and phospholipase A2 in autistic spectrum disorders. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 71(4), 201–204.

Bjørklund, G., Meguid, N. A., Hemimi, M., Sahakyan, E., Fereshetyan, K., & Yenkoyan, K. (2024). The Role of Dietary Peptides Gluten and Casein in the Development of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Biochemical Perspectives. Molecular neurobiology, 61(10), 8144–8155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-024-04099-3

Careaga, M., Hansen, R. L., Hertz-Piccotto, I., Van de Water, J., & Ashwood, P. (2013). Increased anti-phospholipid antibodies in autism spectrum disorders. Mediators of inflammation, 2013, 935608. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/935608

Gimpl, G., & Fahrenholz, F. (2002). Cholesterol as stabilizer of the oxytocin receptor. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1564(2), 384–392.

Hartman, R. E., & Patel, D. (2020). Dietary approaches to the management of autism spectrum disorders. Advances in Neurobiology, 24, 547–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30402-7_19

Khashan, A. S., & O’Keeffe, G. W. (2024). The impact of maternal inflammatory conditions during pregnancy on the risk of autism: Methodological challenges. Biological Psychiatry Global Open Science, 4(2), 100287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsgos.2023.100287

Lemer, P. (2014). Outsmarting autism. Tarentum, PA: Word Association Publishers.

Sharp, W. G., Berry, R. C., McCracken, C., Nuhu, N. N., Marvel, E., Saulnier, C. E., … Jaquess, D. L. (2013). Feeding problems and nutrient intake in children with autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis and comprehensive review of the literature. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(9), 2159–2173.

Taniya, M. A., Chung, H. J., Al Mamun, A., Alam, S., Aziz, M. A., Emon, N. U., Islam, M. M., Hong, S. S., Podder, B. R., Ara Mimi, A., Aktar Suchi, S., & Xiao, J. (2022). Role of gut microbiome in autism spectrum disorder and its therapeutic regulation. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 12, 915701. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.915701

Vancassel, S., Durand, G., Barthélémy, C., Lejeune, B., Martineau, J., Guilloteau, D., … Chalon S. (2001). Plasma fatty acid levels in autistic children. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 65(1), 1–7.

Yu, Y., Huang, J., Chen, X., Fu, J., Wang, X., Pu, L., Gu, C., & Cai, C. (2022). Efficacy and safety of diet therapies in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Neurology, 13, 844117. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.844117

- Nutrition, Neurodiversity, and Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Integrative Approach to Gut and Brain Health - February 16, 2026

- Botanical Allies for Depression and Traumatic Stress: When the Nervous System Needs More Than One Solution - February 6, 2026

- Amino Acids: The Building Blocks for Mental and Physical Health - February 4, 2026

Are You Ready to Advance Your Career?

If you want to advance your career in integrative medicine, explore my courses and certifications.