Sodas—both sugar-sweetened and “diet”—are often among the first substances eliminated in integrative nutrition and mental health care. While many people turn to diet sodas believing they are a safer alternative to sugar, research increasingly suggests that artificial sweeteners may disrupt metabolism, brain health, and gut function in profound ways.

Non-caloric artificial sweeteners (NAS) are among the most widely used food additives worldwide, consumed regularly by both lean and obese individuals. They are commonly marketed as safe and beneficial because they contain little to no calories. However, despite their widespread use, scientific evidence supporting their long-term metabolic safety remains limited and controversial. Importantly, artificial sweeteners do not cease to be additives simply because they are calorie-free; they are bioactive compounds designed to interact with taste receptors, metabolic signaling, and the gut environment.

Diet sodas commonly contain excitotoxins such as aspartame, substances that overstimulate neurons and can negatively affect the nervous system. Ironically, rather than preventing metabolic disease, regular consumption of diet sodas has been associated with weight gain, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Artificial sweeteners, including saccharin, sucralose, and aspartame, have been shown to disrupt the gut microbiota and alter glucose metabolism, even in people without prior metabolic disease (Suez et al., 2014).

In addition, many sodas are high in caffeine, which can exacerbate anxiety, insomnia, irritability, and nervous system dysregulation, especially in individuals already under chronic stress. Regular consumption of sugar-sweetened soda has been linked to DNA damage, increased risk of liver cancer, and shortened lifespan (Zhao et al., 2023). From a public health and clinical perspective, soda consumption represents a significant and often underestimated risk factor.

Why Artificial Sweeteners Can Harm the Gut and Metabolic Health

Artificial sweeteners were originally designed to provide sweetness without calories, but this design overlooked a key biological reality: the body does not respond to sweetness based on calories alone. Sweet taste receptors are present not only on the tongue, but throughout the gastrointestinal tract. When artificial sweeteners activate these receptors without delivering actual energy, they can confuse metabolic signaling and disrupt normal glucose regulation.

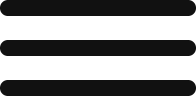

One of the most important mechanisms involves the gut microbiota, the trillions of microorganisms that live in the intestines and play a central role in digestion, immune regulation, inflammation, and brain function. Research shows that artificial sweeteners such as saccharin, sucralose, and aspartame can alter the composition and function of gut bacteria, reducing beneficial species while promoting microbial patterns associated with inflammation and metabolic disease. This imbalance, known as dysbiosis, interferes with how carbohydrates are processed and how insulin signals are interpreted.

A landmark study demonstrated that consumption of non-caloric artificial sweeteners can directly induce glucose intolerance through microbiome changes, even in people without diabetes (Suez et al., 2014). In this study, the metabolic effects were transferable via the microbiota itself, showing that artificial sweeteners act indirectly—by reshaping gut bacteria rather than by supplying calories. Over time, this microbial disruption contributes to insulin resistance, unstable blood sugar, and increased risk of type 2 diabetes.

Artificial sweeteners may also impair the production of short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate (Coccurello, 2025), which are essential for maintaining the intestinal barrier, reducing inflammation, and supporting metabolic and brain health. A weakened gut barrier allows inflammatory molecules to enter the bloodstream, increasing systemic inflammation and further disrupting glucose and nervous system regulation.

Beyond metabolism, the gut microbiota communicates continuously with the brain through neural, hormonal, and immune pathways. When artificial sweeteners disrupt this communication, people may experience increased cravings, dysregulated appetite, anxiety, mood changes, and difficulty with satiety. This helps explain why diet sodas often fail to support long-term weight control and may paradoxically increase dependence on sweet tastes.

From a clinical and integrative perspective, the issue is not simply that artificial sweeteners lack calories, but that they are active food additives capable of altering biological systems that evolved to respond to real food. Understanding their effects on the gut microbiota helps clarify why replacing sugar with artificial sweeteners does not necessarily lead to better health—and may, in some cases, make metabolic and mental health outcomes worse.

Aspartame®: A Widely Used but Highly Controversial Sweetener

Aspartame is one of the most widely used artificial sweeteners worldwide and is commonly found in sugar-free sodas, chewing gum, and low-calorie foods. Chemically known as L-aspartyl-L-phenylalanine methyl ester, aspartame is typically produced using genetically modified bacteria. Once ingested, it breaks down into methanol, which is subsequently converted into formaldehyde, a highly reactive compound. Even at low levels, chronic exposure to formaldehyde has been shown to damage the nervous and immune systems and to cause irreversible genetic damage over time.

A growing body of research links aspartame to serious neurological, psychiatric, and metabolic health effects (Czarnecka et al., 2021). Studies associate aspartame consumption with depression, irritability, migraines, oxidative stress, diabetes, seizures, blindness, obesity, and neurological disorders (Lindseth et al., 2014). In addition, research suggests that aspartame—along with other food additives—may contribute to behavioral changes, headaches, chronic pain, and panic symptoms, likely through its effects on excitatory neurotransmission and neuroinflammation. Aspartame has been identified as a chemical carcinogen in rodent studies (Landrigan & Straif, 2021), and in 2023, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified it as “possibly carcinogenic to humans.” While this classification does not imply immediate danger from occasional use, it raises important concerns about long-term, habitual exposure.

Certain populations appear to be particularly vulnerable to aspartame’s effects, including people with a history of depression, pregnant and lactating women, older adults, and young children (Walton et al., 1993). From a preventive and ethical standpoint, minimizing exposure in these groups is especially important, particularly given the availability of safer, non-synthetic alternatives.

Sucralose®: A Chlorinated Sweetener with Toxic Potential

Sucralose®, commonly known as Splenda®, is another widely used artificial sweetener found in sugar-free beverages and processed foods. Chemically, sucralose is a chlorinated compound, structurally related to other persistent environmental chemicals, including DDT. This chlorination makes sucralose highly stable and resistant to breakdown, allowing it to pass through the digestive system largely unmetabolized, but not without biological effects.

When chlorinated compounds like sucralose are processed in the body, they may generate toxic byproducts that place additional stress on hepatic detoxification pathways and xenobiotic metabolism. Beyond detoxification concerns, a growing body of research suggests that sucralose can disrupt gut microbiota composition, reduce beneficial bacterial populations, and promote low-grade inflammation (Bian et al., 2017). Human and animal studies have linked sucralose consumption to altered glucose tolerance, impaired insulin sensitivity, and changes in metabolic signaling, even in healthy individuals without prior metabolic disease (Ruiz-Ojeda et al., 2019). These findings challenge the assumption that sucralose is a biologically inert or metabolically neutral sugar substitute.

The Hidden Challenge of Soda Withdrawal

Reducing or eliminating soda intake is not always simple. Withdrawal commonly involves symptoms related to sugar dependence, artificial sweetener dependence, and caffeine withdrawal, including headaches, fatigue, low mood, and cravings. Soda drinking is also a deeply ingrained habit, frequently tied to work routines, productivity culture, and emotional regulation. Addressing soda consumption, therefore, requires not only nutritional education but also behavioral and psychological support.

Healthier Alternatives: Reclaiming Beverages as Nourishment

Rather than relying on artificially sweetened beverages, many clinicians encourage people to rebuild their relationship with drinks by choosing mineral water and natural flavorings. This approach supports hydration while avoiding the metabolic and neurological consequences of artificial additives.

Simple alternatives include sparkling mineral water flavored with frozen fruit, fresh citrus, honey, monk fruit, or a few drops of stevia. These options provide sensory satisfaction without the same degree of physiological disruption and can ease the transition away from soda.

Raspberry Lime Rickey: A Naturally Sweetened, Soda-Free Refreshing Drink

This refreshing drink is an adaptation of a New England classic summer favorite and has helped many people successfully withdraw from cola and other soft drinks.

Makes 1 serving

Ingredients

- Crushed ice

- Juice from 1 lime

- ½ cup frozen raspberries

- 1 glass of sparkling mineral water

- 1–5 drops liquid stevia or monk fruit, or dark agave syrup to taste

Directions

Fill a glass with ice. Add lime juice, raspberries, sparkling water, and sweetener. Stir gently to combine and enjoy.

Conclusions: Why These Details Matter

Understanding these details is essential. Artificial sweeteners and diet products are often perceived as neutral—or even beneficial—simply because they contain few or no calories. However, the evidence suggests otherwise. Non-caloric sweeteners remain food additives with biological activity, capable of influencing gut bacteria, metabolic signaling, and neurological function. The absence of calories does not make a substance metabolically or neurologically inert.

Digestion is a highly complex, dynamic process that is intimately connected to brain function, emotional regulation, and mental health. The gut–brain axis plays a central role in mood, cognition, stress resilience, and metabolic balance. Substances that disrupt the intestinal microbiota or alter glucose signaling can therefore have far-reaching effects well beyond digestion alone.

In the new edition of my book, Nutrition Essentials for Mental Health, I explore these connections in greater depth, examining how everyday dietary choices—including additives, sweeteners, and ultra-processed foods—shape mental and emotional health. This second edition expands on the foundational principles of the original book, offering enhanced, practical strategies for integrating nutritional science directly into clinical practice, along with accessible recipes designed to support both metabolic and mental well-being.

References

Bian, X., Chi, L., Gao, B., Tu, P., Ru, H., & Lu, K. (2017). Gut Microbiome Response to Sucralose and Its Potential Role in Inducing Liver Inflammation in Mice. Frontiers in physiology, 8, 487. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00487

Coccurello R. (2025). Disrupting the Gut-Brain Axis: How Artificial Sweeteners Rewire Microbiota and Reward Pathways. International journal of molecular sciences, 26(20), 10220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262010220

Czarnecka, K., Pilarz, A., Rogut, A., Maj, P., Szymańska, J., Olejnik, Ł., & Szymański, P. (2021). Aspartame-True or False? Narrative Review of Safety Analysis of General Use in Products. Nutrients, 13(6), 1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061957

Landrigan, P. J., & Straif, K. (2021). Aspartame and cancer – new evidence for causation. Environmental health : a global access science source, 20(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-021-00725-y

Lindseth, G. N., Coolahan, S. E., Petros, T. V., & Lindseth, P. D. (2014). Neurobehavioral effects of aspartame consumption. Research in nursing & health, 37(3), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21595

Ruiz-Ojeda, F. J., Plaza-Díaz, J., Sáez-Lara, M. J., & Gil, A. (2019). Effects of Sweeteners on the Gut Microbiota: A Review of Experimental Studies and Clinical Trials. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 10(suppl_1), S31–S48. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmy037

Suez, J., Korem, T., Zeevi, D., Zilberman-Schapira, G., Thaiss, C. A., Maza, O., Israeli, D., Zmora, N., Gilad, S., Weinberger, A., Kuperman, Y., Harmelin, A., Kolodkin-Gal, I., Shapiro, H., Halpern, Z., Segal, E., & Elinav, E. (2014). Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature, 514(7521), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13793

Walton, R. G., Hudak, R., & Green-Waite, R. J. (1993). Adverse reactions to aspartame: double-blind challenge in patients from a vulnerable population. Biological psychiatry, 34(1-2), 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3223(93)90251-8

Zhao, L., Zhang, X., Coday, M., Garcia, D. O., Li, X., Mossavar-Rahmani, Y., Naughton, M. J., Lopez-Pentecost, M., Saquib, N., Shadyab, A. H., Simon, M. S., Snetselaar, L. G., Tabung, F. K., Tobias, D. K., VoPham, T., McGlynn, K. A., Sesso, H. D., Giovannucci, E., Manson, J. E., Hu, F. B., … Zhang, X. (2023). Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Liver Cancer and Chronic Liver Disease Mortality. JAMA, 330(6), 537–546. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.12618

- Nutrition, Neurodiversity, and Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Integrative Approach to Gut and Brain Health - February 16, 2026

- Botanical Allies for Depression and Traumatic Stress: When the Nervous System Needs More Than One Solution - February 6, 2026

- Amino Acids: The Building Blocks for Mental and Physical Health - February 4, 2026

Are You Ready to Advance Your Career?

If you want to advance your career in integrative medicine, explore my courses and certifications.